Below is the Corn Exchange Bank from 1929 to 1936.

Members

-

Topics

Archives

-

-

Recent Posts

-

-

-

Investor Education

Market Return After Exceptional Years

Dollar Cost Averaging Tool

Dow Theory: The Formation of a Line

Dividend Capture Strategy Analysis

Golden Cross – How Golden Is It?

Debunked – Death Cross

Work Smart, Not Hard

Charles H. Dow, Father of Value Investing

It's All About the Dividends

Dow Theory: Buying in Scales

How to Avoid Losses

When Dividends are Canceled

Cyclical and Secular Markets

Inflation Proof Myth

What is Fair Value?

Issues with P-E Ratios

Beware of Gold Dividends

Gold Standard Myth

Lagging Gold Stocks?

No Sophisticated Investors

Dollar down, Gold up?

Problems with Market Share

Aim for Annualized Returns

Anatomy of Bear Market Trade

Don’t Use Stop Orders

How to Value Earnings

Low Yields, Big Gains

Set Limits, Gain More

Ex-Dividend Dates -

-

Historical Data

1290-1950: Price Index

1670-2012: Inflation Rate

1790-1947: Wholesale Price Cycle

1795-1973: Real Estate Cycle

1800-1965: U.S. Yields

1834-1928: U.S. Stock Index

1835-2019: Booms and Busts

1846-1895: Gold/Silver Value

1853-2019: Recession/Depression Index

1860-1907: Most Active Stock Average

1870-2033: Real Estate Cycles

1871-2020: Market Dividend Yield

1875-1940: St. Louis Rents

1876-1934: Credit-New Dwellings

1896-1925: Inflation-Stocks

1897-2019: Sentiment Index

1900-1903: Dow Theory

1900-1923: Cigars and Cigarettes

1900-2019: Silver/Dow Ratio

1901-2019: YoY DJIA

1903-1907: Dow Theory

1906-1932: Barron's Averages

1907-1910: Dow Theory

1910-1913: Dow Theory

1910-1936: U.S. Real Estate

1910-2016: Union Pacific Corp.

1914-2012: Fed/GDP Ratio

1919-1934: Barron's Industrial Production

1920-1940: Homestake Mining

1921-1939: US Realty

1922-1930: Discount Rate

1924-2001: Gold/Silver Stocks

1927-1937: Borden Co.

1927-1937: National Dairy Products

1927-1937: Union Carbide

1928-1943: Discount Rate

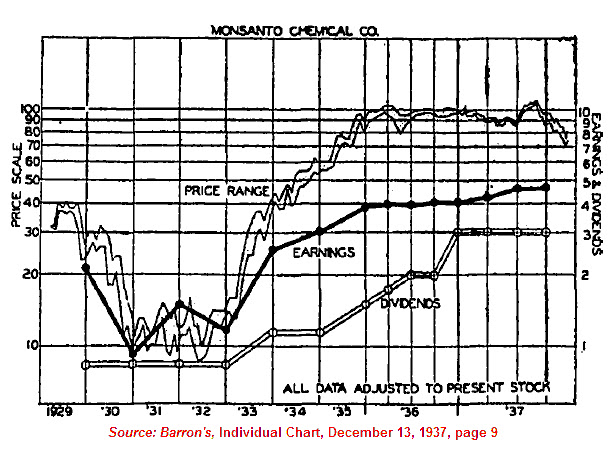

1929-1937: Monsanto Co.

1937-1969: Intelligent Investor

1939-1965: Utility Stocks v. Interest Rates

1941-1967: Texas Pacific Land

1947-1970: Inventory-Sales Ratio

1948-2019: Profits v. DJIA

1949-1970: Dow 600? SRL

1958-1976: Gold Expert

1963-1977: Farmland Values

1971-2018: Nasdaq v. Gold

1971-1974: REIT Crash

1972-1979: REIT Index Crash

1986-2018: Hang Seng Index Cycles

1986-2019: Crude Oil Cycles

1999-2017: Cell Phone Market Share

2008: Transaction History

2010-2021: Bitcoin Cycles -

Interesting Read

Inside a Moneymaking Machine Like No Other

The Fuzzy, Insane Math That's Creating So Many Billion-Dollar Tech Companies

Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Letters

Forex Investors May Face $1 Billion Loss as Trade Site Vanishes

Why the oil price is falling

How a $600 Million Hedge Fund Disappeared

Hedge Fund Manager Who Remembers 1998 Rout Says Prepare for Pain

Swiss National Bank Starts Negative

Tice: Crash is Coming...Although

More on Edson Gould (PDF)

Schiller's CAPE ratio is wrong

Double-Digit Inflation in the 1970s (PDF)

401k Crisis

Quick Link Archive